Because I have so many canvas panels of proportions set by today's standards such as

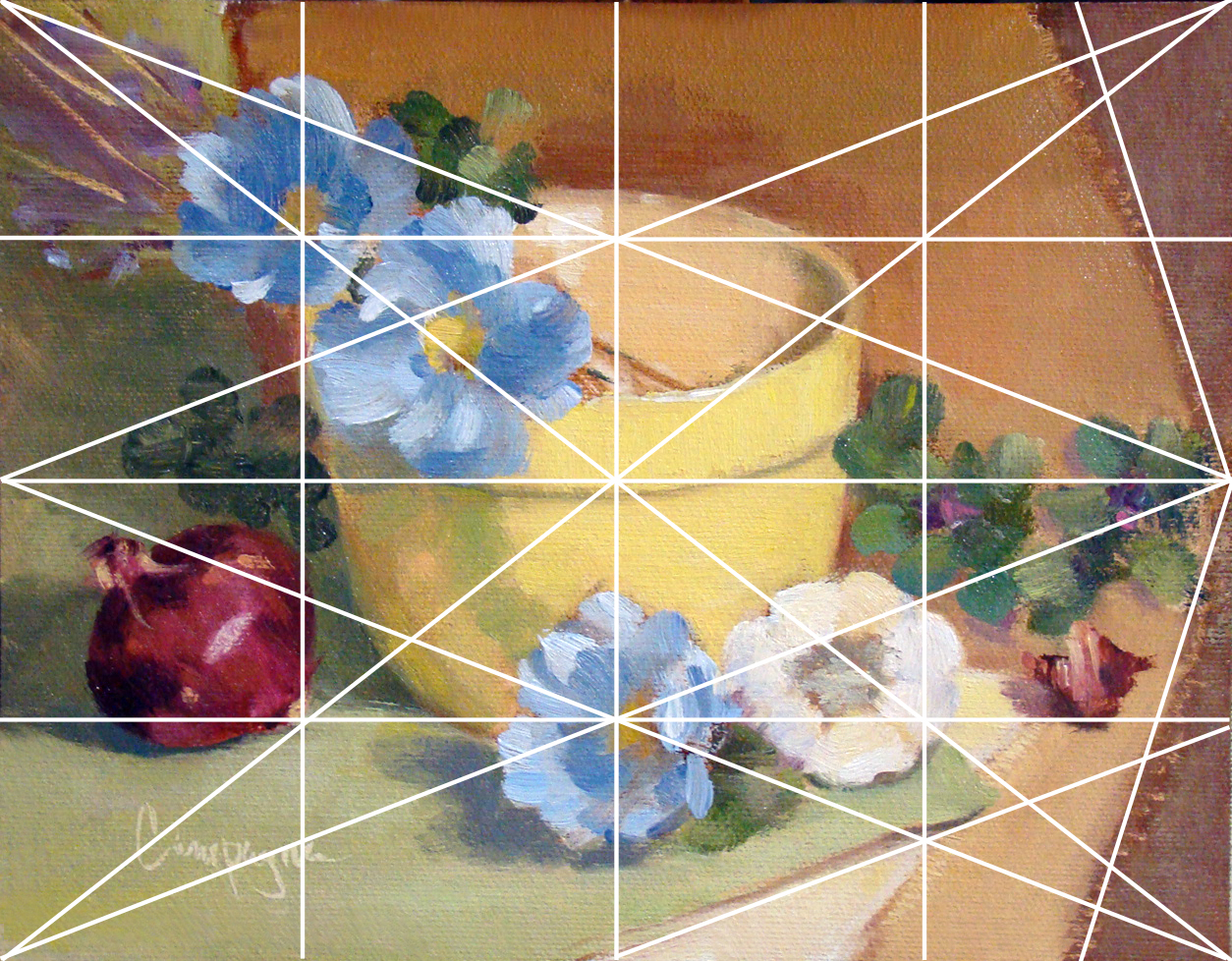

6 x 8, 8 x 10, etc., I decided to simply use a grid that would divide the space by similar means without going to the phi rectangles, and root rectangles as the Masters did. This grid is known as a 'harmonic armature'.

So in my simple way this painting is the result selecting random objects placing along the grid lines.

|

| Yellow Bowl I 9 x 7 Oil on Canvas Panel © 2013 |

The canvas panel was an 8 x 10 cut down to 9 x 7 inches; the color palette includes ultramarine blue, cad scarlet, cad yellow light and quinacridone magenta, and white - It is not a true use of the Fletcher system, but I did consider it when choosing the colors.

So back to the classical geometry...

When I did graphic design, grids were used to help arrange elements on the page for readability, and sometimes we tried to squeeze in a little something for visual interest that was less rigid. In this situation I just went with the grid similar to what the old masters may have used in designing their compositions.

This next image shows that grid superimposed to demonstrate what I mean. I did not consider the 'do not' put things in the middle of the picture plane, and 'do not' divide the picture plane in half. I just did what the grid suggested with an occasional 'offset' to keep from getting a headache. ;o)

| ||||

| Grid_Yellow Bowl for demonstration purposes. |

Since I did this painting myself using basic information, it is a little difficult to critique as good or bad. Of course, I do wonder what may have happened with this layout if I was not using a grid. My first thought is I may have put the bowl to the left and made other decisions about placement for the remaining objects. I do think I may be able to get more depth of field by changes in proportions with or without the grid - hmmmm.

There are other grid options of course, but I just went with 4, 8, etc. Eventually, I will attempt one in thirds and follow a similar breakdown - perhaps using like objects to see if the result is noticeably different.

As I get more comfortable with this way of looking at composition I will learn to include arches and semi-circles to move the eye through the picture plane, my hope is to create images that are more visually compelling for the viewer.

In any case, I welcome your feedback and hope you enjoyed this little demo on using a basic grid.